Moving Beyond Christian Democracy

Christian Democracy is no longer the only option for Catholics these days.

For quite some time, it appeared that Catholics have had a clear political option: Christian Democracy appears to have been by far the one and only alternative for those who wish that their faith informs their politics. This was particularly true during the Cold War era, when a rather peculiar union sacrée was formed, that of Liberals and Catholics, to fend off the encroachments of the sceptre of Communism. This partnership was intellectually explained by Jacques Maritain and politically manifested itself in the form of Christian Democratic parties. At first, it appears that everything was running rather smoothly and Christian Democrats had been the key figures behind the European integration, providing for a continent that respects the human person and brings in a new era of peace to the European continent.

Apart from Maritain and his concept of integral humanism, this ethos was espoused also by Michael Novak in his Spirit of Democratic Capitalism and has soaked through and through the works of George Weigel .

Watering down of Christian Democracy

However, there is a catch. And namely, that Christian Democratic parties gradually became more and more Democratic and less and Christian. A brilliant book by Vladimír Palko titled The Lions Are Coming documents this watering down of the Christian Democrats throughout Western Europe, on their surrender even in the questions of life and death - such as protecting the most vulnerable yet unborn and the elderly.

The collapse of the Christian democratic substance can be explained by several factors. The Second Vatican Council has led the Catholic Church away from being an impregnable bastion of faith more to becoming a bridge towards the modern society. The result of course meant that rather than the Church leading the faithful closer to a Christian understanding, the modern Catholics led the Church closer to the modern society. And since a demoralised, modernised postconciliar Catholicism could no longer provide a bastion to which its champions could retreat to, the traditionalists were subdued by a neomarxist wave in the late 1960s. This approach to Christian politics has presided over the deepest erosion of what remained of a Christian society - judging by its fruits, it was nothing other than a long defeat, to paraphrase Tolkien1

Furthermore as the threat of Communism vanished, the liberals no longer needed to make common cause with the Christian democrats and attacked their ci-dévant allies heads on with the culture wars. Since then, the unrelenting defense of the Christian anthropology appears not only as a lost cause within public political discourse, but also inside many of the Christian Democratic parties themselves. Many have become tasteless shells of their former selves, dull clubs of status quo centrists. A handful of others are facing uneasy choices and appear to be searching for a healthy example to follow.

Deneen´s 4 Quadrants

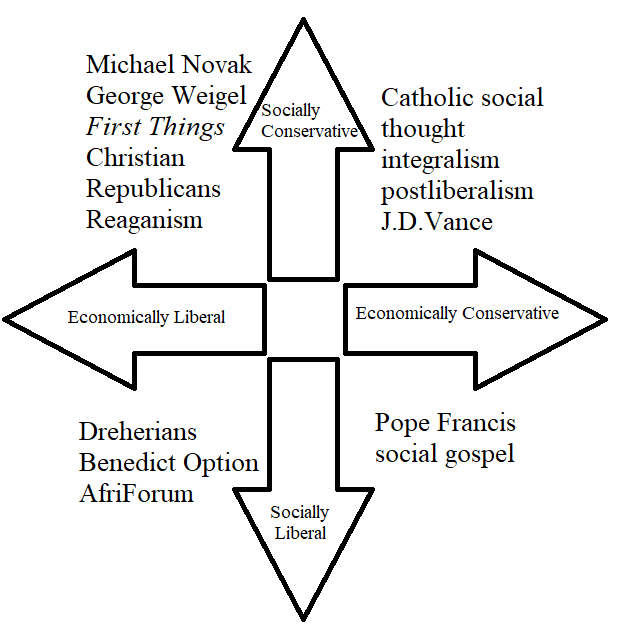

So what are the alternatives ? To better approach this topic, I´ll use a variant of the political compass as rethought by Patrick Deneen, author of Why Liberalism Failed2 I´ve slightly altered the layout of the quadrants. The horizontal axis is the economic one. On this one, I have put the laissez-faire liberals on the left, while a conservative , gaullist sort of approach would be understood as economically conservative. On the social axis, social conservatives demanding the adherence do divine (or natural) law and obeying God´s Commandments in the upper quadrants while those who seek not to impose their understanding of rightful conduct unto others on the lower half of the chart.

The upper left corner is what can be best summed up in the American context as the Republican party while in Church - the policies that I´ve described above based on the understanding of Maritain, Weigel and the Reagan era. Pushing for laissez-faire economics while attempting to maintain a socially conservative public space.

In the lower left corner we get the Benedict Option3 folks: the Dreherians who have given up on imposing their ideas unto the broader society and functionally want to be just allowed to do their own thing. A very successful manifestation of this type of approach would be of course the AfriForum way of doing things - not seeking to improve things by the ballot box but rather through community federalism and grassroots-level engagement4.

The lower right corner is what I suspect is where Pope Francis and quite a lot of Latin American clergy witnessing poverty daily are located, with their focus on the social gospel. Ultimately, this can in the end result in a “liberation theology” mindset and is hardly distinguishable from socialism.

And then finally there is the upper right quadrant, which is where one could fit the entire pre-Vatican II Catholic social teaching, integralism and its present-day renaissance in the postliberal articulation. Indeed I would actually assume that the new American vice-president is over here as well.

Which of these approaches works best?

The Quadrants and their Shortcomings

Taking the upper left corner risks reducing the very content of Christian politics to a handful of moral questions, namely in the initiatives in the broader pro-life advocacy. A politician then champions this cause by taking up the banner and attempting to make some advances in this one field of action, while heroically receiving devastating blows from one´s political opponents. It resonates with the image of the romantic hero, outnumbered and outgunned, championing a lost cause. The trap of limiting oneself to this narrow scope of action, with little to no economic solutions is manifest.

The Dreherian approach may result in either in fatalistic resignation from seeking any meaningful engagement in politics, since the end is nigh and the Titanic is gonna sink anyway. Or the more active, diligent approach, in building resilient community institutions and testing alternatives small-scale. If the Titanic is gonna sink, why not rather build rafts that can save us, should the society-at-large be doomed anyway?

The social gospel and preferential option for the poor risks to be effectively socialism in a Christian cloak. It risks simply of appealing to two emotions - compassion and envy -becoming a mere activism at best and transmuting into Christian SJWism at worst. As such, it risks to reducing the Christian element in politics to mere charity.

The postliberal approach however, provides a coherent series of answers on a broad variety of issues, thereby averting the short-comings of the other competitors. It has a distinct vision of a well-ordered society committed to the common good and informed by Christian anthropology, backed by an intellectual tradition of Catholic social teaching and a centuries-old natural law school of thought.

Nevertheless, it is not without its own shortcomings. The thorough secularisation of many nations makes it difficult to imagine a restauration of a religiously-informed society. How is this to be met by the atheist, the agnostic and the immigrant, if this aproach is met with hostility by quite a few Catholics themselves? Is it feasible in modern societies of the 21st century? If so, is it not a utopian idea? If not, is it not mere theoretical daydreaming?

Clarity of Vision

These are, of course, valid remarks. The question whether any approach in politics can succeed is legitimate, but the only way of truly finding out is putting it to the test, rather than dismissing it outright.

The appeal of the postliberal approach is, that unlike the other ones, it in fact provides a clear vision of what to strive towards, of how a well-ordered society ought to look like and which considerations ought to be taken account in any hypothetical issue. Its proposal of a clear coherent vision is something that makes it deeply appealing today, in political landscapes dominated by dull uniparties.5

In an era of shallow marketing-driven and performance-based politics, postliberalism offers something very unique: depth, substance and vision. This very advantage of its own has been criticised by its opponents, as if it were to be something to be ashamed of.

Quite the contrary. Unlike the Christian in politics from the top-left quadrant, it greatly increases its breadth and risks in no ways to become a three-topics platform, while it largely increases also the scope of action in comparison to the Benedict-Optioners.

Where postliberalism shines is in its clarity of purpose. In an era of shallow marketing-driven politics, offering a coherent vision rooted in truth and the common good is not just a strength—it is a moral imperative. Even if its realisation in the fullest remains questionable, it still provokes us on how to achieve the Good, the True and the Beautiful in public life, and inspires action, rather than resignation.

A Few More Steps

As such, postliberalism is in a position to become a powerful player. Nevertheless it still has quite a few quirks to perfect, and its success will depend precisely on them. Will it be able to inspire practical hope, rather than nostalgia in a weary world? Will it be able to translate abstract principles into concrete solutions that work?

In a mechanical, technocratic world, postliberalism will need to actually prove its solutions and be able to point to them as results achieved, similar to how Christian theology had to articulate itself using the form-language of Greek philosophy, were it to claim predominance in the Mediterranean. So too will postliberalism need to have a track record to succeed. It may need to try out at the local level, working very closely with some of those resilient Benedict-Option communities to develop and fine-tune viable solutions, that could then be applied more broadly.

TOLKIEN, John Ronald Reuel: “Actually I am a Christian,” Tolkien wrote of himself, “and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’— though it contains (and in legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory” (Letters 255). (link)

DREHER, Rod : The Benedict Option

The term uniparty is used to refer to a situation, in which there are nominally several political parties, but their agendas in terms of practical policy proposals are next indistinguishable.

it likely cant thrive or propose solutions in a "mechanical, technocratic world" but it could -- possibly easily -- propose solutions that undo the great post war errors and make the world no longer mechanical and technocratic, and that is a world that would have places it can thrive in...

I think you are right in that we are approaching an inflection point, where old models of conservative approaches have run themselves dry in the liberal world. Where early 2000s were shaking off the Cold War, and 2010s hit us full in the face with progressivism, 2020s are where the post-liberal order is finally being shaped. More and more people question the approaches that got Christian Democrats only the long defeat, and perhaps we can start,steppibg beyond the paradigm set for us by the left. The language of the conversation is changing and we should make an effort to make it a driven, purposeful process, lest we get lost in the search itself and give ground to civilisational regressives again.