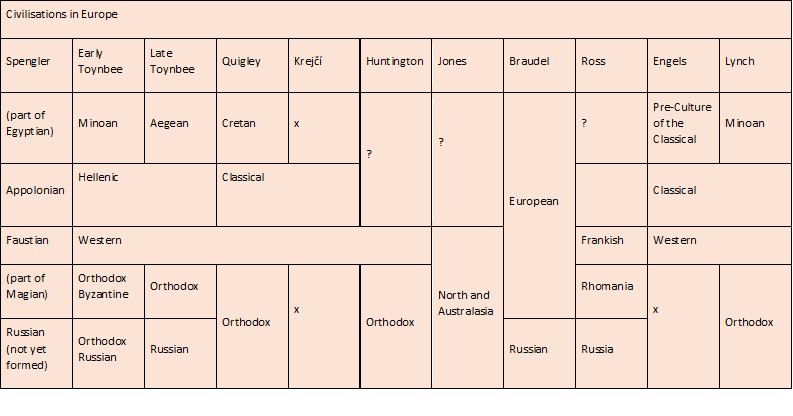

After reviewing the catalogues of individual authors, it is time to make a comparison according to the continents. The oldest civilisation we encounter is the Minoan/Aegean/Cretan civilisation, which, however, is viewed as a separate civilisational entity only by Toynbee and Quigley. For Toynbee, the universal state of the Minoan (later Aegean) civilisation is the "thalassocracy of Minos," while Quigley rather perceives the Mycenaean Empire as such . Spengler, like Engels, views Minoan Crete as a satellite civilisation of the Egyptian one, while Mycenaean Greece is seen as a pre-cultural phase of the development of Classical civilisation. However, there is general agreement on recognizing the Apollonian/Hellenistic/Classical/Ancient/Greco-Roman civilisation as separate, with the Roman Empire being its universal empire. Kelley Ross wrote about the current state, paraphrasing the opening words of Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico: " Europa est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam Romaniam, aliam Franciam, tertiam Russiam.[1]"

The civilisations of the African continent seem to have been overlooked by many authors. All authors recognize the uniqueness of Egyptian civilisation; both Toynbee and Krejčí also acknowledge its Nubian periphery as a separate civilisation. The Phoenician colonies on the North African coast, led by Carthage, represent not a local civilisation that emerged on the African continent, but for Quigley, they represent the universal empire of Canaanite civilisation. For Toynbee, after the plundering of Baghdad, a separate Arab civilisation began to emerge between Al-Andalus and the Levant. Regarding indigenous civilisations south of the Sahara, most authors overlook their histories; the most lenient in this regard is Rudyard Lynch, who is willing to admit the civilisational identity of Ethiopia and the Sahel. On the other hand, Jaroslav Krejčí, when evaluating Sub-Saharan Africa, writes that the rise and fall of various geopolitical formations, which Africanists call kingdoms or even empires, evokes more the impression of kaleidoscopic swirling than any discernible trajectory[2].

Categorizing civilisations on the Asian continent is quite complex, with the most debatable being the classification of the rich tapestry of civilisations in the Middle East. Some authors (early Toynbee and Engels) propose dividing Mesopotamian history into two civilisations, while others view Mesopotamian history in its entirety as the story of one civilisation. The history of the Hittites can rightfully be considered the story of its own independent civilisation.

The most difficult challenge is the division of monotheistic civilisations of the Orient. Toynbee postulates the story of a unified Syriac civilisation, which perhaps begins with Joshua and the Book of Judges, and whose lament is the weeping over Baghdad, plundered by the Mongols. At the same time, a millennium of history, from Alexander's conquerors of the Orient to the rise of Islam, is viewed in this perspective as an interrupted song, a time of interregnum. Where Spengler sees unity of form — the Magian nations in their own expression of political form — Toynbee sees failed attempts to establish their own abortive civilisations, as in the Monophysites or Nestorians. However, he overlooks the chosen people of the Old Testament, as well as the gifted Phoenician sailors, whom Quigley and Krejčí appreciate as their own Canaanite or West Semitic civilisation, which lived its days from the invasion of the Sea Peoples to the defeat at Gaugamela.

How should we categorize the civilised histories of peoples reciting the shahada? Is it one civilisation, or did Toynbee correctly see two civilisations divided by the waters of the Euphrates — the Arab and Iranic ones? Why does Jeff Jones today separate the Persian and Turkic components of this civilisation into two distinct macro-regions?

On the Indian Subcontinent, we can clearly distinguish the history of the Indus Valley civilisation from the later Indo-Aryan societies on the subcontinent. For Toynbee, its later history is the story of two civilisations — Indic and Hindu — separated by the invasion of Hellenized Hunas from the northwest. This view seems isolated. However, how should we approach the countries influenced by Indic, particularly Buddhist, influences? Should we view Tibet, Indochina, and the Malay Archipelago as distinct civilisational entities, or as part of the same civilisation? Krejčí rightly observed the period of pan-Indian unity, which later fragmented, with each of its peripheries following its own historical path, with Islam accompanying these developments on the islands.

Like South Asia, East Asia is for the earlier Toynbee written as two successive Chinese civilisations. The main dividing point is the collapse of the Han dynasty, on the ruins of which a new Chinese civilisation later arose. Among the countries under Chinese cultural influence, Japan deserves the most attention, as it can truly be considered a distinct, self-sustaining civilisation. Some might say the same about Korea and Vietnam, but caution must be exercised here, and premature conclusions should be avoided.

In our survey of the catalogues of the histories of civilisations on the Asian continent, we find a similar pattern. These are the histories of civilisations whose cultural influence at the height of their glory extended widely into neighbouring regions, after which a crisis occurred and only the core of the civilisation (e.g., India and China) continued into a new phase of civilisational development, while the periphery from that point on followed its own trajectory (e.g., Tibet, Japan, Korea...).

We will skip over Oceania. For the early Toynbee, civilisation's seeds sprouted on the Polynesian islands, but they did not bloom or bear mature fruit. The islands of Oceania form, according to Jones, a distinct cultural macro-region, which he called the South Pacific. However, it seems that human societies in these maritime regions did not reach the level of a high civilisation.

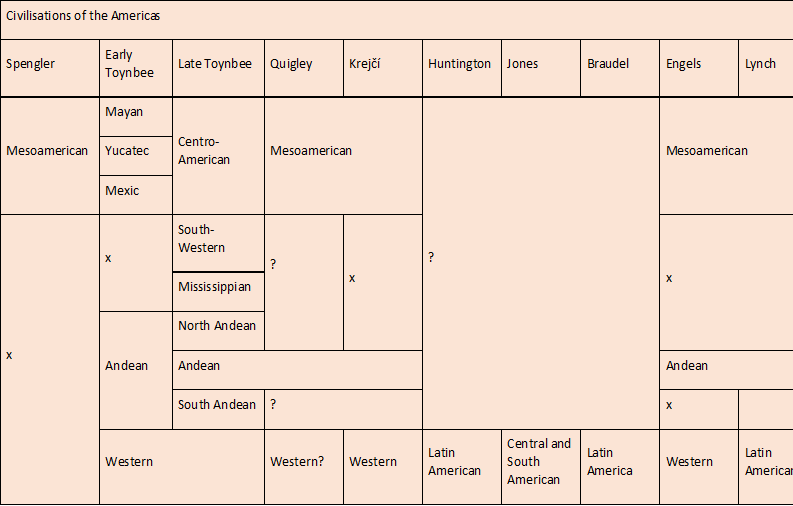

After crossing the vast and endless waters of the Pacific, we arrive at the American continent. Here, even the strictest authors acknowledge the creativity of the indigenous cultures in Mexico and (with the exception of Spengler) along the Andes mountain range. In pre-Columbian Americas, however, the attentive Toynbee sees more civilisations: in his early concepts, he identifies three civilisations in Mexico — the Maya, and then their two successors — the Mexic and Yucatec civilisations. In his final catalogue, he eliminates this tripartite division and finds four additional societies he recognizes as civilisations: the first in the Mississippi River basin, among the mound-building societies and cities like Cahokia; the second, which he called "Southwestern," among the Pueblo Indians along the upper Rio Grande and in neighboring regions of so-called "Oasisamerica."

He finds two more in South America — the "Northern Andean" among the Chibcha in Colombia and the "Southern Andean," referring to the advanced societies in northwest Argentina and northern Chile.

[1] Europe is divided into three parts, one of which is Romania, another France, and the third Russia. ROSS, Kelley: Guide and Index of World History, Dynasties and Lists of Rulers.

[2] KREJČÍ, Jaroslav: Postižitelné proudy dějin, p. 268